In a 2020 interview, high profile fashion journalist and former Vogue editor André Leon Tally said, “Dame Anna Wintour is a colonial broad… she’s part of an environment of colonialism. She is entitled and I do not think she will ever let anything get in the way of her white privilege.”

Tally was reacting to Wintour’s email apology for the “mistakes” in her 32-year Vogue tenure—namely: not doing enough to elevate Black voices and publishing images that were racially and culturally “hurtful or intolerant.”

Coincidentally, Wintour’s email was sent two weeks after the death of George Floyd, and one day after Samira Nasr was announced as the new editor-in-chief of U.S. magazine Harper’s Bazaar—making her, a woman of color, the new face of Wintour’s competition.

“‘Wokefishing’ [..] describe[s] the phenomenon of people pretending to hold more progressive views than they really believe or practice, in order to ensnare potential partners.”

But why is this so interesting now? Because it reflects an attitude that emerged last year and that has since become widespread: “wokefishing.” The term first appeared in a July 2020 Vice article to describe the phenomenon of people pretending to hold more progressive views than they really believe or practice, in order to ensnare potential partners. “A wokefish may at first present themselves as a protest-attending, sex-positive, anti-racist, intersectional feminist who drinks ethically sourced oat milk and has read the back catalogue of Audre Lorde,” writes Serena Smith, the author of the Vice article. Smith first noticed this behavior on dating apps where, for example, men would use #feminist in their bios, but upon closer examination their treatment of women told an entirely different story. “Or, as is often the case, they are actively the opposite in their personal lives. It’s sort of like catfishing, but specifically with political beliefs,” she says.

The same day Wintour sent out her public statement, she also missed a race and racism meeting at Vogue. Her email received widespread backlash, with many noting that during the many decades she has been at the head of the fashion industry, she seemed content with its focus on thin, white cis-women—until she was called out. Wintour was accused of “wokefishing.” Since then, the term has been adapted to different situations, and gave rise to a myriad of new forms. “Blackfishing,” for example, is a popular derivative to describe a white person using tanning, makeup, fashion and hairstyles to appear to be of mixed heritage. Similarly, “wokefishing” evolved from its usage on U.S. dating apps and into capitalism, eventually making its way to the other side of the world.

The politics of the fashion game

The global Black Lives Matter movement, ignited by the death of George Floyd in the U.S.A., strongly resonated in Germany, where Fashion Africa Now is based. Protests in multiple cities across the country helped bring a heightened awareness about issues of institutional and structural racism. The new climate forced many other German fashion companies to reflect on their corporate philosophy and culture, questioning, essentially: “How diverse are we?”

The majority was quick to find an easy fix: the use of Blackness. More Black models in campaigns, so that the fashion company looks beautifully diverse—when, in fact, German fashion institutions, universities and companies are sorely white. Fashion magazines started to feature more designers of African descent, with the rare presentation of the “Black Owned Brand.” There has also been more social media emphasis on BIPOC people and, of course, the “tokenism” to appease the Black quota—symbolic gestures to ensure the appearance of diversity. All of these tactics, however, could be broadly described as “wokefishing.”

Let’s be honest: it’s not that simple. Facing institutional and structural racism requires dealing with the violent colonial past. The German fashion industry is shaped by Western ideals of authority of interpretation—norms that have existed and that have been globally perpetuated for decades. It is high time that we critically question this system and structures.

“We need to ask: what beliefs and values is this industry built on? [...] The inexorable exploitation of raw materials and labor continues to this day, and all of this goes hand in hand with the prosperity of the Global North.”

We need to ask: what beliefs and values is this industry built on? Fashion as we know it was erected on the exploitation and oppression of Black people, who were the cheap labor force in indigo, cotton and many other plantations that produced the basic materials of this industry. These people were oppressed and dehumanized, while Africa was robbed of its raw materials such as gold and diamonds, alongside a variety of other vital resources.

The inexorable exploitation of raw materials and labor continues to this day, and all of this goes hand in hand with the prosperity of the Global North. The greed for profit of the Global North and the subsequent dependence of the Majority World lead to inhumane conditions along the fashion supply chain. It is an unbalanced, unhealthy and corrupt basis that needs to be dismantled. For that, we need to get to the roots and pull them apart.

Wokefishing vs. Fashion activism

If the fashion industry really wants to engage in this effort, it needs more than sustainable fashion concepts or individuals with alibis. In this context, companies like to claim sustainability, but what does that mean in concrete terms? It is not enough to produce fabrics and collections under partial socio-ecological standards. It takes much more—an admission that farmers who produce cotton are paid fairly, that industrial parks in African countries pay their employees fairly, that decision-makers in purchasing, marketing and sales are sensitized to buy collections from BIPOC; and that representatives of BIPOC sit in relevant lead positions.

The fashion industry needs to explore business models rooted in circularity and longevity. It needs to go further and it needs to be deconstructed down to the smallest individual parts, so that something new can grow. How the international fashion industry defines sustainability does not relate to how sustainability is defined in Africa. It is time to rethink and restructure old thought patterns.

“In Africa [...] the movement has embraced a much more holistic understanding of sustainability: Redefine, Reclaim, Reimagine and Revolutionize. In order to implement this movement, it requires the expertise of BIPOC in all aspects.”

The African fashion industry has been playing out in the slow fashion market, where the environment, producers and consumers have always been the focus. In the West, the sustainability movement is characterized by the so-called four Rs (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle and Rot). In Africa, however, the movement has embraced a much more holistic understanding of sustainability: Redefine, Reclaim, Reimagine and Revolutionize. In order to implement this movement, it requires the expertise of BIPOC in all aspects.

Wokefishing in fashion?

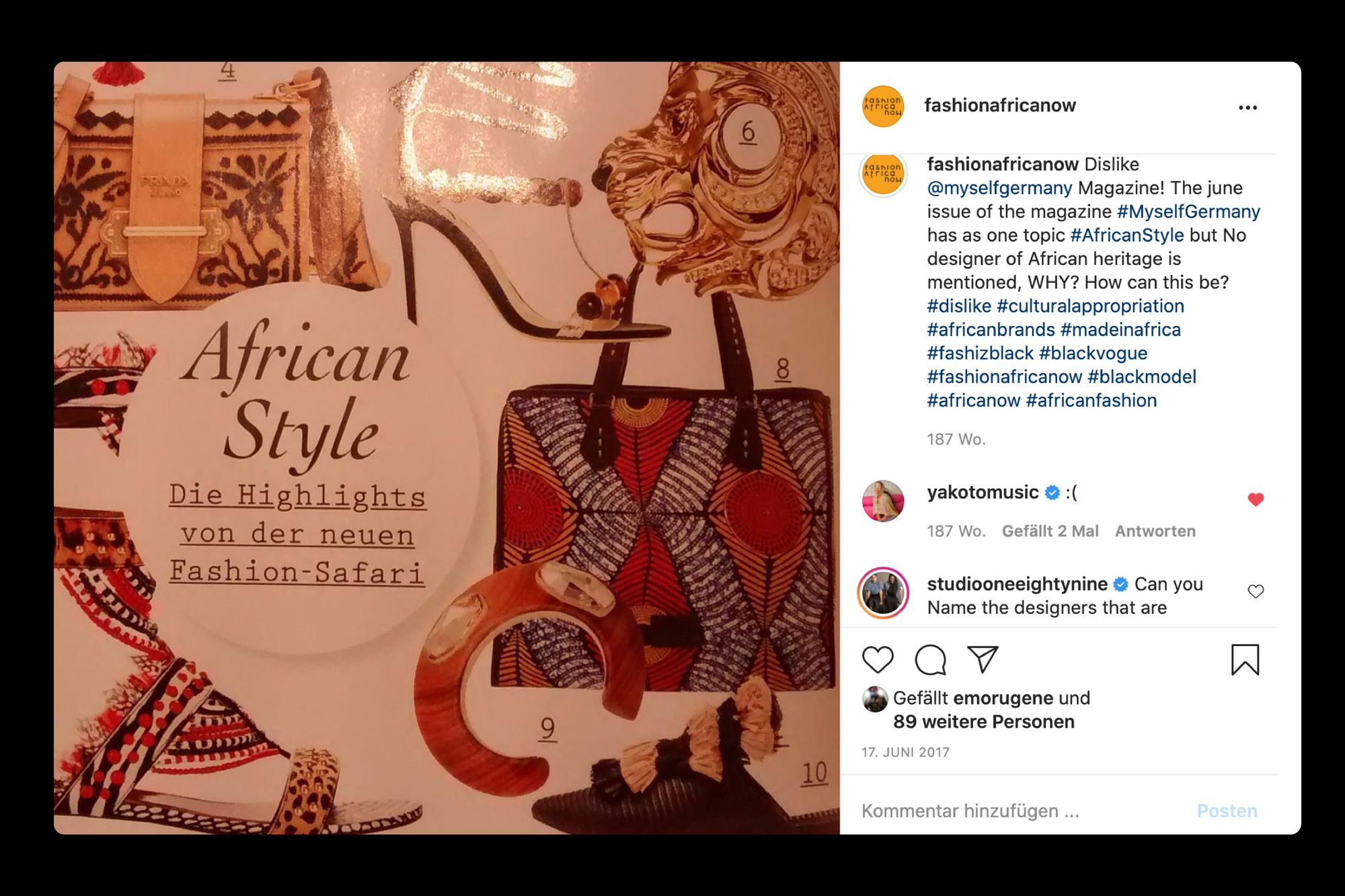

The fashion industry sorely lacks diverse perspectives. When BIPOC or African expertise comes into play, unfortunately it is often diverted back to “wokefishing.” An example is Myself Magazine: in their June 2017 edition, they highlighted African Styles, yet unfortunately no African or diasporic fashion brand was mentioned. The term “African Styles” was only used to describe the theme of the month, and to highlight Western brands that help themselves to African aesthetics and unabashedly use it for cultural appropriation. Obviously, it was not the intention of the magazine to present brands or designers of African heritage. We—that is, the collective of Fashion Africa Now—called them out on social media, and still have not received a response.

Another example is Elle Germany: in their November 2019 issue, the magazine was meant to celebrate Black models. It featured a white model on the cover and the issue was titled “Back to Black—Black is back again—irresistibly.” Within the pages of the magazine, two black models were misidentified: Joan Smalls, a globally established top model, who has been in the industry for nearly a decade, was presented as a newcomer. The internet reacted immediately as Elle made it look as if Blackness was a trend that had only now just come back. The scandal drew international attention, with industry icons like Naomi Campell posting on social media about their disappointment to see a major fashion publication put out something so thoughtless.

In the wake of the global BLM protests last year, many German brands posted black squares on their social media accounts in accordance with the Blackout Tuesday hashtag. What has happened in Germany since then? As far as we know, an e-commerce retailer is looking into onboarding brands from designers of African heritage, but that’s about it. The KadeWe Group used to stock brands by Black designers, but they have since stopped. At the moment, there are only a few stores that stock African brands in the entire country. It is not enough to just stock a few brands. Until there’s real acknowledgement of systemic racism, real change is not possible.

The expertise of Fashion Africa Now lies in African fashion. Our activism started in 2012, at a time when there was little interest or acknowledgement of “Made in Africa” and contemporary African fashion (in fact, it was still mistaken for “Ethno fashion”). In the last ten years, we have strived to push for change in Germany, and have been actively introducing brands like Adama Paris or Maxhosa to the German fashion landscape. Today, African Fashion is somehow perceived, but is still not yet acknowledged on a large scale. In the past we heard a lot about the new pledge of improvement and promises of diversity, inclusion and representation that we became familiar with over recent years. Few actually realized that the first step to being anti-racist is to analyze their own behavior and workforce.

Reflection and Circular Economy

The wealth of knowledge from BIPOC, however, is indispensable in the process of exercising diversity, inclusiveness and representation. The actors, critical thinkers and activists who practice alternative or new business models should be taken seriously. It is time for circular fashion and awareness for the environmental impact of the clothing industry. The international fashion industry has to admit that change can only happen with a rejection of hegemony—specifically, the inclusion of BIPOC in relevant leadership positions, and the acceptance of new solutions from non-Western perspectives.

The process involves critical engagement and reflection. Reflection can only succeed if there is insight and a serious will for positive change. As stated by Dr. Mahret Ifeoma Kupka, fashion curator at the Museum Angewandte Kunst in Frankfurt: “Ignorance cannot be an excuse, but must trigger a serious debate and a learning process, otherwise we will not get anywhere as a community.”

“With regard to people who work in fashion, the danger is that they are capitalizing on movements and communities that they are not really supporting. The actual work should be activism.”

Overall, wokefishing seems to be a product of the idea that one can simply pretend to go with the times. Social media enables individuals and brands to create personas, but these personas can be “woke” without actually contributing anything to a movement. It is extremely “surface level” participation to post an infographic, and then continue going on as usual. With regard to people who work in fashion, the danger is that they are capitalizing on movements and communities that they are not really supporting. The actual work should be activism; it’s not enough to hide behind a company. The time for change is now, and change can only be reached by looking into the issues and confronting them.

White folks: Stop controlling the narrative! It is time to change it, share it and allow Black voices to add their experience to the conversation. How to start?

Beatrace Angut Oola (she/her) is an interdisciplinary fashion curator, creative producer, African Fashion advocate and lecturer, based between Hamburg and Kampala. She has spearheaded the conversation around inclusivity, curated exhibitions in Germany and worked on knowledge exchange projects in African countries and has also championed best in class practitioners in the diaspora. In 2012, she launched the first high-end fashion platform for Black designers (Africa Fashion Day Berlin) and founded the creative agency APYA Productions in Germany.