Some ideas lodge themselves in a corner of our mind, gently brewing for years until they’re ready to take shape. In a sense, the idea for Swatch Bharat —a digital gallery launched by Kasol-based graphic designer and podcaster Kawal Oberoi, to document and celebrate Indian native visuals or “desi aesthetics”—took root long before the project came to life. When Oberoi was growing up in the late 1990s, long before the waves of globalization washed through the country, much of India’s graphic landscape was tinged with local visual idiosyncrasies. The wrappers of the candies he bought from the neighborhood store in Pathankot—a small city in Punjab where he spent his summer vacations with his cousins—were designed locally. Bespoke hand-painted signages hung near shop fronts; the facades of temples, parks and schools brimmed with murals painted by local artists; and water tanks in the neighborhood took on bizarre shapes such as bodybuilders, footballs, and airplanes. “There was a sense of local identity and unique aesthetics—often playful, sometimes gaudy, but never boring or mass-made,” Kawal explains. “The siloed nature of the places during those times produced various visual dialects that were distinct to each neighborhood. But with each passing year, this was changing.”

At the close of the decade, the rise of digital printing and the onslaught of globalization triggered a change in the local landscape: the homegrown graphics and native flourishes were quickly being replaced by a more “modern” Western aesthetic. Oberoi and his generation witnessed this eclipse, which stirred a sense of “fear and frustration” that became the two driving forces of this documentation project.

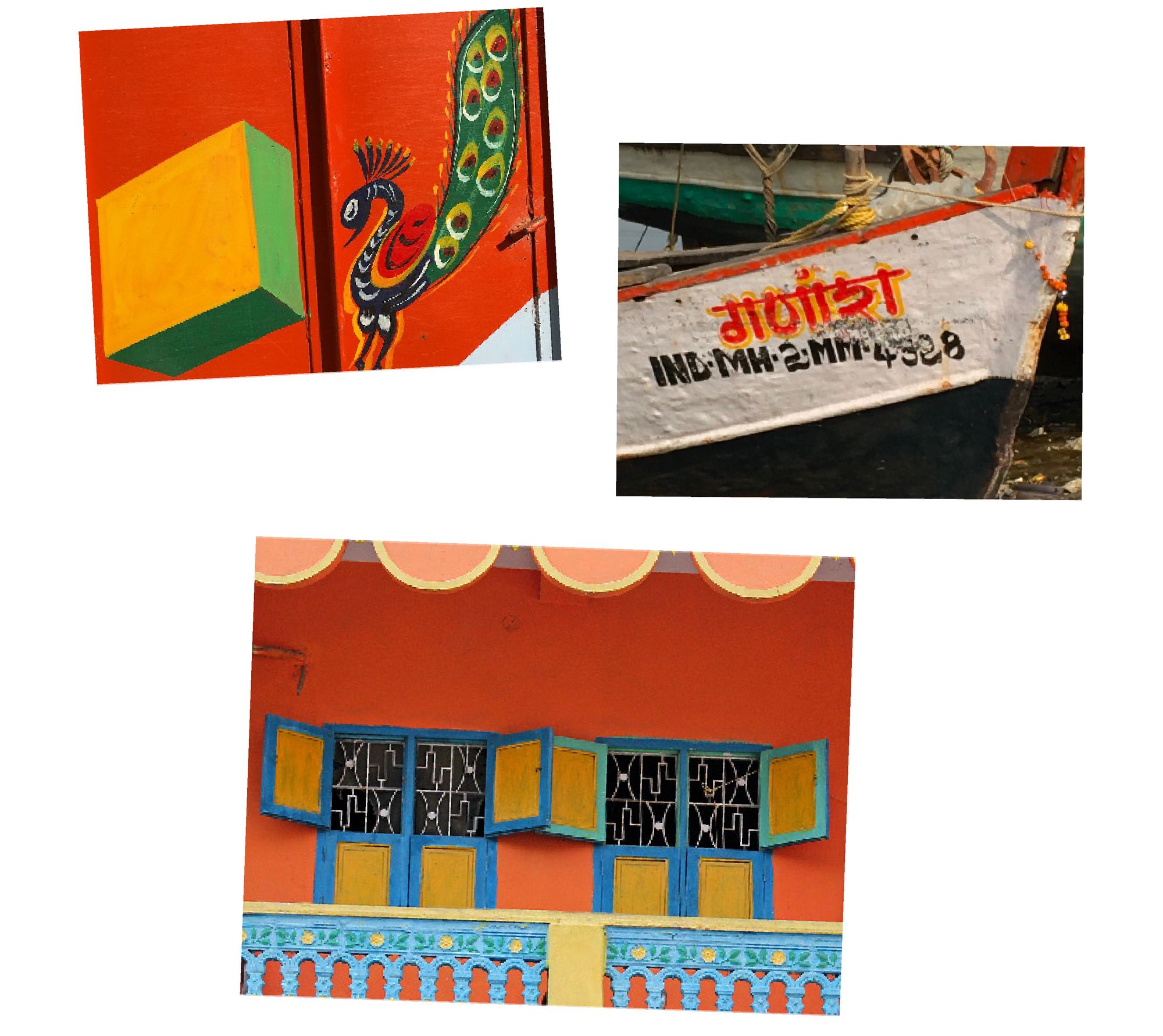

Launched in 2017, Swatch Bharat currently lives in a corner of the internet as a visual collage of images from the streets and homes of India, created as a springboard of inspiration for designers, illustrators and visual artists. In its nine series, Swatch Bharat takes visual notes from far-flung corners of the country, from the hand-painted motifs on a truck in Himachal Pradesh and the hand-lettering on a fisherman’s boat in Mumbai, to the bright, searing colors on the facades of homes in Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu.

The “fear and frustration” that was brewing since Oberoi’s childhood had only deepened by the time he launched the project. “The fear of losing expressions of ‘desi (local or indigenous) aesthetics’ we see around India to the Western aesthetics brought in by globalization,” he notes, adding: “The fear is quite real, as a lot of what you see in Swatch Bharat has been replaced, repainted or discarded by people.” The project is equally rooted in the frustration of “seeing typical Indian elements and style being reinterpreted by fellow designers and ad agencies.” In the last decade or so, the tired tropes of cutting chai, mustaches and turbans became ubiquitous motifs seen across contemporary branding and graphic design projects in India. “I felt that this could be due to the lack of online reference points for desi aesthetics created by Indians themselves,” notes Oberoi.

“The fear of losing expressions of ‘desi aesthetics’ [...] is quite real, as a lot of what you see in Swatch Bharat has been replaced, repainted or discarded by people.”–Kawal Oberoi

Swatch Bharat, which was created as a reaction to this frustration, had its humble beginnings in a childhood scrapbook. “During my summer vacations, I would visit my cousins, and most of our time was spent loitering in the winding lanes of their neighborhood in Pathankot, eating locally-made candies and playing with locally-made toys. I remember I had an extreme fondness for the wrappers of those local candies and the packaging for the toys. I would spend all my pocket money on them and collect the wrappers and snippets of packaging in a scrapbook,” he reminisces.

With the gradual erosion and the loss of “desi” aesthetics across the cultural fabric of India, each consecutive summer, Oberoi would have fewer things to collect for his scrapbook. The local candies were swiftly being replaced by the rising popularity of Parle and Cadbury’s, and local toy companies were being shouldered out by cheaper, made-in-China alternatives. Suddenly, modernism became aspirational, and the neighborhoods and streets were visually sanitized to upgrade the urban landscape. “Things started looking like they could be from anywhere around the world. It is easy for me to romanticize the old, but the new was better in many ways. The candies didn’t cause stomach ache as often, and the toys didn’t break as easily, but I always had this feeling that we lost something in this transition,” says Oberoi. “We could have gotten all the benefits of modernity without giving up the ‘desi-aesthetics.’ I feel that’s where my frustration with this change started. I began collecting and archiving pictures of my encounters with desi aesthetics and the visual dialect of different places in India.”

“We could have gotten all the benefits of modernity without giving up the ‘desi-aesthetics.’ I feel that’s where my frustration with this change started.”–Kawal Oberoi

Echoes of these unique, local visual idioms are seen across Swatch Bharat. Teeming with vignettes from the streetscapes, Oberoi’s collection documents the many nuances of local architecture, murals seen across cities in India, and varied examples of craftsmanship, from artisans weaving bamboo baskets to engraved patterns on stone walls of historic monuments. But look closely, and it’s impossible to miss the recurring images of hand-painted signages on shop fronts, advertisements and local buses. Often blending pictograms and typography to create illustrated posters—like this sign created for a fish fry stall—hand-painted signages once defined the language of the streets of India.

The signboard painter emerged as a local designer during India’s long struggle for freedom and the rise of the Swadeshi movement, which encouraged the use of local, homegrown products over imported goods. Striking hand-painted signages, menus and advertisements highlighted local goods and services, and granted each city and neighborhood a unique visual language, with signs often painted in multiple local scripts, like Devanagari, Tamil and the Bengali-Assamese script. However, with tectonic shifts in the Indian economy in the early 1990s and the rise of the cheaper, easier alternative of digital printing, hand-painted signs and the vocation of these incredibly talented, often self-taught painters, were gradually lost to the folds of time. Other factors were at play too: Coca-Cola, and many other international brands, began handing out free signages to local shops in a standardized design, and local government by-laws in cities like New Delhi outlined restrictions on size and style of lettering for signages in an attempt to “modernize” the cityscape. Never documented historically as an artistic practice, the nuances of the profession and the many disappearing hand-painted signs were gradually lost to history.

But such losses are not a matter of the distant past. “There was a hand-painted Pepsi advertisement at the Ludhiana railway station in Punjab that I used to love,” noted Oberoi. “Somewhere between 2015-2016, I was passing the station and I noticed it had been replaced with a printed vinyl flex banner. That’s when the fear of losing this visual culture became real. I felt the urgency to preserve my collection of pictures and showcase it somewhere, and also to encourage others to photograph and preserve their observations. That’s when I decided to turn this idea into Swatch Bharat.”

Since then, many of the design ephemera documented in the project have disappeared. Oberoi suspects that the painted smartphone signage in Series 4, shot in 2018, might be lost today. “The owner of the shop told me that he’s changing his business,” he says, adding: “The pink-and-blue painted sweetmeat shop counter in Series 7, documented in the same year, might also get replaced soon; the shop owner moved that wood-and-glass case behind the store, and a new metallic counter with refrigeration has been pushed to the front of the shop.”

The swatches—often shot in candid, awkward angles—hint at the immediacy of the project, which in itself is a race against time to archive these visual nuances before they’re lost or replaced. The urgency of this archival process is something that other creatives felt too; they reached out to Oberoi to contribute their own images to the collection. “When I launched the project, it received an overwhelming response from other designers. Apparently, there were many creatives who had collections of similar images, and some of them asked if they could contribute to the gallery on my site,” he notes. “I loved the idea. For me, it’s a gallery anyone can refer to, relish, and learn from.” To date, fifteen creatives have contributed to the gallery.

In the course of it all, the original intention of the project has been met too: the ever-growing collection has served as a pool of inspiration for emerging designers. “A friend of mine, who is an illustrator, told me that he constantly referred to Swatch Bharat for an entire month while working on a project, to draw visual notes on a particular region of India,” says Oberoi. “Personally, I like to deconstruct individual images to get insights into the details of different regions and their idiosyncratic visual cultures. You won’t see a direct borrowing of elements from these images in my work, but the insights are very much present.”

“For me, it’s a gallery anyone can refer to, relish, and learn from.”–Kawal Oberoi

The vision of the future is for the project to grow into an online gallery that’s searchable by region, elements, culture, and language; and for it to become a platform for critical discourse and offer essays and research that dig into the layered, textured history of indigenous Indian design. But at the heart of it all is an urge to “appreciate and collect these nuances of visual culture,” as Oberoi says—to take a moment to pause, and reflect on what’s already around us.

Ritupriya Basu (she/her) is a writer and self-confessed "design maniac" based in India. Through her work, she digs into the intersection of design, culture, and undocumented histories lost to the folds of time. Her words have appeared in Eye on Design, It's Nice That, Broccoli Magazine, Varoom, Stack Magazines and WePresent.

Kawal Oberoi (he/him)is an independent graphic designer, brand consultant and podcaster from India. He works with clients ranging from artists to writers, start-ups to established businesses, corporates to not-for-profit organisations, boutique studios to established agencies and brands that are in-between.

In 2018, he started Designed this way podcast. It’s his initiative to start candid conversations with designers and other creative folks, to bring out the stories about the realities of living a creative life. These wide-ranging conversations also reveal the diversity of thoughts, practices and opinions that exist in the creative world.

He lives a nomadic lifestyle and travels around India capturing expressions of Indian native aesthetics. He shares them with the world through his passion project, Swatch Bharat.

All photos courtesy of Swatch Bharat.

Title image: Hand-lettering on blue bus (Kolkata, West Bengal) by Sukriti Sahni.